The future: Scenarios and vignettes Robert Swigart. 1.* - unedited transcript - I am primary

interested in story telling. I come to this not as an engineer, but as

a fiction writer with an interest in what is going to happen because human

beings have always wanted to know what is going to happen. One of the tools

that a lot of people use in business environments, and in our research

is the scenario process. How many people here are familiar with scenario

planning. That is quite a few. I'll skim over this stuff pretty fast

because I am interested in my addition to it.

Very briefly then, what is a scenario, when you get a team together and you start to build a scenario, you want to have a lot of different people with a lot of different input that begin to generate a story. So people will start to say if such and such happens then this will. You start to get a snippet of a story. A cause and effect relationship. You collect a lot of those, condense them together, and your snippets build into a story line. We try to say that all of these factors interrelate, and you build what a story is. You get that nailed down, everything is logically and internally consistent, and you make a scenario out of it. So a scenario is a way of anticipating. It is not predictive. Your are not forecasting, you are creating a set of options. What might happen, and make it useful. In business planning or anticipating what is going to happen. So I prefer, instead of saying complex planning, since we live in a world in which planning seems to get thrown out before it can come into fluation. I call it strategic anticipation. Being ready for might happen, rather than planning for what you are erroneously convinced will happen. So a scenario is a historical memory of the future. It is something in which you can sit down and read and say this is a consistent story of what might happen. I remember that this is sort of a future thing. Experience tells us that for scenarios, for different options of the future, work the best. Two is ok, the problem with three.... there was an exercise once in Thailand where they said, let's get a group together and decide what would be the best future for Thailand, the worst future for Thailand, and what they would think would be in the middle somewhere. Everybody gravitated toward the middle one. You want to challenge people by creating a number of scenarios that don't allow for that black hole gravity well. In which people tend to fall. You also don't want to create scenarios about what you hope will happen. In thinking about the future there is a certain time horizon up to which you can be fairly confident that you can forecast. That there is a high degree of certainty or a low degree of uncertainty. A fairly high number of predetermined things that you are fairly sure are going to happen. There comes a point where those things begin to decay. Uncertainty increases and the predetermines begin to disappear. The possibility of surprises increases, things come out a blind side you. That is the area in which you want to start thinking about scenarios, where you start creating alternatives. There is another break point further beyond that where you move into the realm of hope. Scenarios aren't going to help much there, usually nothing will. Usually these things are a few pages long, too long and you loose people's attention. Too short and they don't contain enough of a story. The ones that I have seen written in third person point of view. I am going to give you an example at the end, a couple paragraphs from a scenario and a couple paragraphs from what I am adding to this. They require constant revision, because the future never gets here. It is constantly changing. So revising the scenarios, or throwing them out and starting over is an unending process.

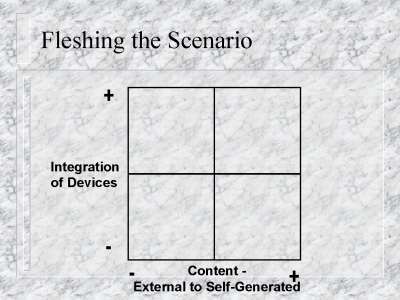

This is the easy way to start building a scenario. Just make a four square, start with something low in the lower corner, something high in the upper and outer corners. See if they fall into four different kinds of stories. So as an example we did a project a couple years ago looking at the evolution of consumer tech particularly computers and things like this. We have low integration of devices that is lots of different kinds of devices in the lower left.

The origin of the content for these devices moving from externally developed, Disney develops all of the content for your pilot moving to self-generated. So you have two coordinates and you can find your own. You try to figure out the kinds of things that you will get. These are the kinds of things that we came up with.

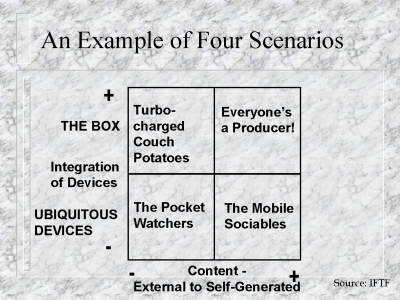

The top row is called the box. Everything gets integrated into one box.

The turbo charged couch potatoes, which is the title of that scenario,

where the people who had big screen TV web access, telephone Internet,

everything hooked up in one box with a giant remote control device. Most

of the content is downloaded via satellite or cable and pumped into

your brain. The right side where you have self-generated content, you have

everybody's a producer. We have access to digital video, audio; we create

our own content ship it via e-mail or the Internet. So everybody is beginning

to produce high quality content. Lower left, pocket watchers. Ubiquitous

devices by full of hand held TVs or palm seven you could call one of the

pocket watch devices. You are connected to a source of information but

it is pumped out to you, not generated by you. The mobile sociable are

the cell phone, pager, palm pilot beaming crowd. With an exoskeleton

of media devices, which I sometimes feel like I am. Then you start to build

a scenario; you start to tell a story about what these things are.

You want to push the story out and make it challenging. Not the obvious

stuff, but try to make it extreme so that when you think about the

future you may decide that one of more of these is not likely and you throw

them out. You need to push that and challenge it before you can decide

that. The fact of the matter is that none of these are going to take over,

it looks like, and they are all going to happen. Then it is a question

of where the weight falls, what is the largest of these domains. If you

are in a technology business this is significant. What I have done

with scenarios now is add what I call vignettes. These are not the high

level, third person, summary stories that scenarios are. Most of

you, if you have read scenarios know that they describe the world they

say in 2004, the oil economy collapsed and global warming took off. These

three or four major events happened and the world begins to look like this.

As a result regulations came in and did that. And so on. You get this

overview.

Vignettes are something that we started to develop about five years ago as little short seams. Little pieces of story that happened inside, we did them inside some reports as a way of illustrating significant points. The first project we did was a study of how people used technology in the household, in Silicon Valley. We came up with about eighteen lessons that came out of some ethnographic interviews. The one I remember best was that people were requiring technology as a sort of social plumage. They weren't actually using the technology that much, but they liked to have it sitting around so that people would admire them for it. A couple of years later we did a global survey like this. We did some ethnographic interviews in a number of countries, on of them was Chile, one of the researchers there reported that it is illegal to speak on a cell phone when you are driving in Chile and fully thirty percent of the people who were arrested for speaking on a cell phone while driving, were using a fake cell phone. That is an illustration of how people use technology as plumage. If you were to create a vignette around that, you would actually have a character in the sense and would see the stuff happening. Vignettes as storytelling with characters and all sorts of other stuff is a way of transmitting cultural information. People learn in different ways. There are people who are very fond of graphs and charts and learn a lot from them. There are other people who like to read analysis. Some people like stories, and I am one of them so it is fun to do it. They are all also more emotionally compelling, at least for me, than graphs and charts. I am not a data person. So what is a vignette? It is a short scene. Originally we kept them

to less than a page. It presents a problem. The character has to overcome

something. There is a challenge that has to be met.

These are basic storytelling elements. It illustrates an important part

in the scenario. So vignettes become a kind of illustration maybe like

a cartoon panel of various aspects of the scenario itself. It shows characters

interacting with each other. Real people in real situations, doing human

things. They use dialogue. People talk to each other and there is communication

going on. They contain emotion and for me the most important reason

to use these things is that they reveal the human meaning of this over

view scenario that you have created. They show how it affects people's

lives.

Now a little about story structure, I love this because it is a formula. An event (E) causes a person (P) to desire a goal (G). This is basic story structure, it goes back to Aristotle. Some of it happens to cause a person to desire a goal. That is why we identify with characters in TV shows, novels, and movies. Basically what happens in a story is P tries to get G until P gets G or gives up or gets run over. Now it gets a bit complicated with the graphics here.

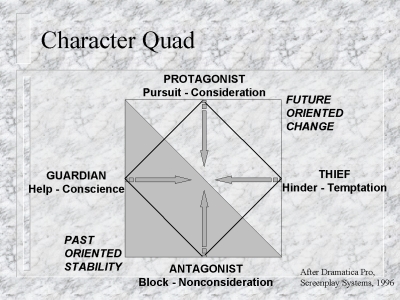

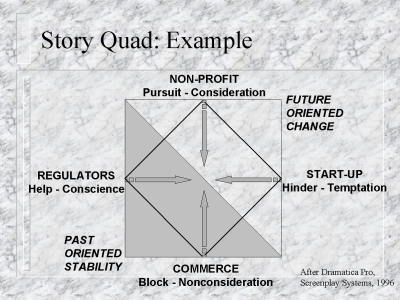

There are four major characters in any story. A satisfying and successful story will have all four of them. I use this a lot because it has turned out to be an extremely useful tool. The protagonist who is the main character, the hero, the star of the story is in pursuit of the goal. They are trying figure out how to achieve the goal, how to get it. How to break into the bank vault or get the girl. That is Luke Skywalker by the way. The antagonist is obviously in opposition to the protagonist, and is trying to block the protagonist from achieving the goal. Or to force the protagonist how to don't consider how to figure it out, or reconsider. There are two characters that are orthogonal to those in opposition to each other. The one on the left is the guardian, OB-1. Helping the protagonist, but also a kind of conscience. A character that tries to keep the protagonist on the straight and narrow. Opposing that is the thief, who is trying to hinder and tempt. You will see the use of this in a minute. The antagonist is the empire, and the thief is actually Darth Vader. Come over to the dark side. Trying to tempt the protagonist off of the path towards the goal. I have added the stuff about past oriented stability and future oriented change because I think when you are doing scenarios this is useful to think about. The antagonist is trying to keep the status quo, maintain things the way that they are, and stop the protagonist from making the change. The guardian represents tradition, represents values, helping but still representing some kind of past. The thief is trying to change things too, but his or her way. The white part of the square is the future. What does this mean for doing scenarios?

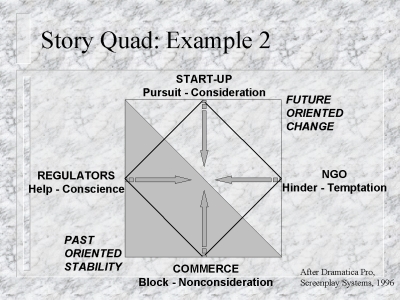

Well if you are going to do a study for a client, whom we do a lot of, you might want to plug the client in for the protagonist role. Let's say for the sake of argument that we are doing a non-profit here. What is trying to stop the non-profit? The for profit, let's say. Maybe the for profit is going to come in and give free housing. The Association of American Realtors doesn't like that. They are in opposition to each other. You have some one who is trying to do something, make a change, and you have someone who is stopping them. Maybe the regulators are on the side of the conscience and help. That is the guardian. Maybe you have some start-ups out here that are not directly opposed to non-profits, but in fact see and opportunity here and want to get around the regulations. They are hindering and tempting. Come over and help us out. We are just a little start up, we need some non-profit. Now the nice thing about this is you can actually rotate this. You could put the regulators up in the top as the protagonist, but I just substituted a couple of others. Let's say your client or business is a start up, and you are worried about how this story might unfold. Then you plug in different characters around this quad. It is very useful, because any good story has to have all four. It is interesting in that it falls out the same as the four squares. Four scenarios, and four characters.

If you figured out what they four major players are, you could rotate

them around and create four different stories with the different protagonists.

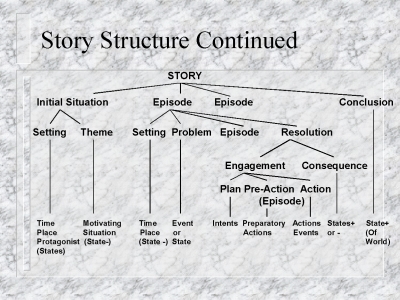

Drama. Drama has a curve. There is an initial situation. That is the event that triggers (P) to want (G). There is a setting, there is a place. That is why it is important. It is a real place that has real meaning for people. It's not the world. It creates a theme. Why are we doing this? What is the message? What domain are we talking about? Is it the ecology of the world or are we talking about markets? What thematically are we looking at? There is an episode. Something happens. Again the episode has a setting and a problem. Then there is a resolution. Does P get G or not?

A little complicated. This is just a graphic depiction of those points.

A story includes all of those. It has the four characters, and it has a

beginning, a middle and an end. It is very convenient; it's a nice three

x structure. Any book on screen writing will tell you they all have three

x. It goes back to Aristotle. I don't believe the hypertext. Post-modernists

will say that you don't have to have them; I think that they are important.

So you have an initial situation. You have an episode, or maybe a series

of episodes, which are like small versions of the over all story. You have

a resolution and a conclusion. Down at the bottom you see the state of

the world. Sometimes the state can go negative on you. If P gives up, or

gets run over by a bus. So I thought I would finish with a quote from one

scenario. From Peter Swartz's book, The Art of A Longview.

This is from a scenario that is called, change without progress. "The change without progress scenario is the dark side of market world, a future of chaos and crisis in which people see themselves as the Lone Ranger fighting the system, and the system falls apart. It is a future similar to the world in the movie Blade Runner; here is a world with fast pace economic activity, but one in which ruthless self-interest and corruption run rampant. Social conflict widening the gap between those who have made it and those who are permanently locked out, and environmental decay are all commonplace. Economic volatility and the disdain for the welfare of average people color pubic policy and corporate practice. There is little threat of big wars, imagine global gang wars instead. Small, short lived, incoherent fights, more and more out of pride and bad temper, then conflicts of real interest. The principle that my enemy of my enemy, is my friend, dominates international politics. Instead of rigid alliances there are quick paced uneasy tense marriages of convenience...." It is just the flavor or this. An overview high level, fast paced summary, third person, no characters. This is from a project that we did last fall. We were trying to look at technology about twenty years out. This is set in 2020. There were four of these stories. We are actually doing vignettes now that are short stories. This is more like four or five pages long. This was well, what is the dark side. We were looking at biotech and this is a story about gene hacking. What are teenagers going to be doing in 2020? They probably won't bring down Yahoo; they'll do something else. This is Columbine the next generation. "Jose Stewart Narcado and Billy Yackmanhan hacked into the gene bank early Saturday morning before any of the watchdog agents were back from the subway attack in Paris, which had rubbed them half over the wrong way. First, who ever did it had hacked a bug that ate pollomber insulation, and then decomposed. Leaving nothing but a few traces of organic molecules. That was one bitchin bug, and you had to admire. Second the electrical short spired off a number of microwave frequencies disrupting not only communication channels, but also all sensor traffic in the sixteenth aroundisment. That was cool too. What wasn't cool was people got killed and hurt. Very uncool. Stewart, aka. Demo Man, resented it. Billy he said, the two of them crouched beside a junction box at the edge of their Buenos Airs neighborhood, we have to do this right. Yeah we got to show them, Billy said. As the youngest he was keeping watch, the soft air hiss of high-speed vehicle traffic was only centimeters away, on the other side of the wall. The story goes on and you see what they do. Again the flavor there is what I was after. I was trying to make it personal, make it real, and make it into a story. That is what I have to say about scenarios today. Questions? Audience: Are you concerned at all about people reading a story, and being unhappy maybe about the style and the nuances, and kind of overlooking the point, which is the scenario that you are putting together? No. I am a good writer. I think that if it is done right, the point of it makes the impression. What we did at the meeting was I read these to a small group. We had about forty people at a workshop and then there was discussion about the stories. There was a lot of material around it, to keep it focused on the story. Audience: I am notorious in this seminar for bringing up law. I can't help in bringing it up again in connection with your comment about story being a powerful mode of communication. The fact that law teaches itself and reproduces itself in the form of stories, otherwise known as cases, is probably the most forgivable thing about the field. If we only sited rules, I think we would have been annihilated a long time ago. No, I think it's true. It's the think that makes law human. It is a human activity. Audience: I'd like you to say a little more about your comment about hope. I'd particularly wanted to say the scenarios are formed out of projecting into the future for possibilities. The reason for doing that is to come back to the president and say what kind of choices that we might make today that can influence those outcomes. I'd like that part of it to be explicit and linked to the notion of...you sort of treated hope like that's way in the future when everything is so misty that all you have left is hope. I would like you to bring the hope into the scenarios as one of the compelling drivers of the choices that we make. That is a great question. The hope, there is a timeframe beyond which your speculating. We don't know what that time frame is. What we do at the institute is try to go five to ten years, and sometimes twenty. In twenty years who remembers what we said. The institute has been putting out a ten year forecast for twenty-one years now. We have outlived the first ten forecast. The results have been actually good. The whole point of doing the scenarios is to make good decisions today. That means to paraphrase and anthropologist friend of mine who said the stories that we tell about the past is a way understanding the social realities of the present. I say that the stories we tell about the future are also another way of understanding the social realities of the present. They don't really tell us about the future, but they tell us how we feel about it. They hopefully make us make better decisions today.

---

Above space serves to put hyperlinked

targets at the top of the window

|

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3 Fig. 4

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

Fig. 5 Fig. 6

Fig. 6 Fig. 7

Fig. 7