|

The Mouse turned 60!

Historic Firsts:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The first mouse prototype |

Doug and team rounded up then best-of-breed pointing devices to evaluate, and rigged up some in-house devices to add to the mix as well, such as a knee-operated device (see Mouse Alternatives below). He also reviewed his earlier notes with lead engineer Bill English, who built a prototype of the hand-held device with perpendicular wheels mounted in a carved out wooden block, with a button on top, to test with the others. This was the first mouse (pictured left and below). These devices were tested on their display workstation running their prototypical interactive text editor (see User's Guide). Watch Doug and Bill (above right) discussing this study and the first mouse.

Check It Out 3

|

Watch a history of the mouse, the dawn of personal and interactive computing |

|

Check out the MouseSite's

Check out the MouseSite's |

Watch how the mouse changed lives Watch how the mouse changed lives |

Visit this digital Mouse Exhibit at the Computer History Museum |

|

Witness the World Debut - watch Doug introduce the mouse, and watch the mouse in action, footage selected from Doug's newly re-mastered 1968 'Mother of All Demos' - and now using your own mouse or alternative, you can 'test drive' the demo interactively, or watch just the Demo Highlights 3a

Watch Doug tell the story in his Designing Interactions interview with IDEO's Bill Mogridge [book], and his 2002 Oral History interview with NY Times' John Markoff for the Computer History Museum. 3b

On Exhibit: visit virtual museum exhibits showcasing his innovations at the Smithsonian Museum, the Computer History Museum, and more. Visit On Exhibit and Special Collections by Institution for details. 3c

Watch "The Computer Mouse" video short on how the mouse changed lives and enabled the personal computing industry to take off and thrive. 3d

Explore the Stanford University MouseSite where you will find images of the first mouse, the US Patent on the Mouse, historic photos from the lab, and much more. 3e

See SRI's Timeline on Innovation: Computer Mouse and Interactive Computing, MIT Press Designing Interactions: Doug Engelbart, Macworld's mouse history timeline, PC Advisor's 40th anniversary timeline, and our History in Pix photo gallery. 3f

Check out the online Exhibit on the Mouse and Keyset at the Computer History Museum, as well as press coverage of their 2001 event "Early Computer Mouse Encounters". 3g

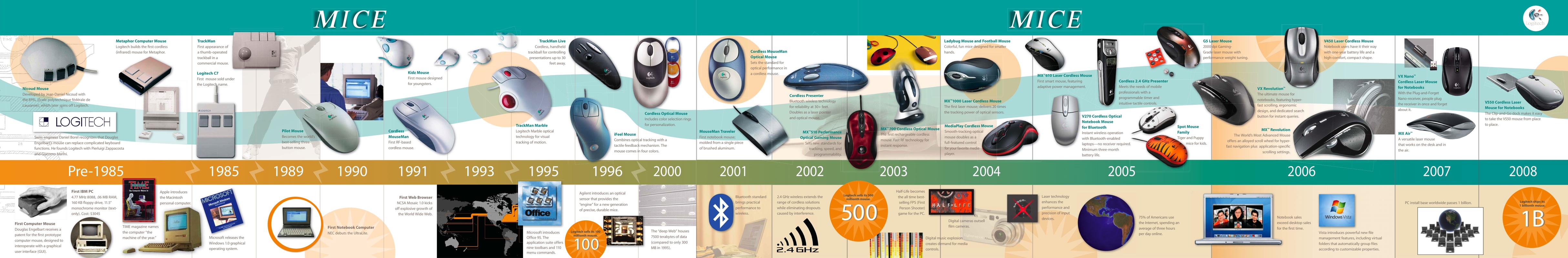

Logitech celebrates "ONE BILLION MICE SOLD!" making headlines in 2008. See their press release, blog post, and billionth mouse celebration page with links to press kits, fun facts, and timelines. The event coincided with our 40th anniversary celebration of Doug's landmark demo, titled "Engelbart and the Dawn of Interactive Computing". Enjoy the following timeline from Logitech's celebrations. 3h

The Mouse Wins 4

In 1965 Engelbart's team published the final report of their study evaluating the efficiency of the various screen-selection techniques. They had pitted the mouse against a handful of other devices, some off the shelf, some of their own making (see Mouse Alternatives below). The mouse won hands down, and was thus included as standard equipment in their research moving forward (see Screen-Selection Experiments below for links to key reports and papers detailing these experiments). In 1967, SRI filed for the patent on the mouse, under the more formal name of "x,y position indicator for a display system," and the patent was awarded in 1970. 4a

The first mouse plugged into it's display workstation

- circa 1964

The first mouse plugged into it's display workstation

- circa 1964 |

Enter, the Keyset: To further increase efficiency, Engelbart's team thought to offer a companion to the mouse – a device for the left hand to enter commands or text while the right hand was busy pointing and clicking (shown above). After trying out several variations, they settled on a telegraph-style "keyset" with five piano-like keys. This keyset also became standard equipment in the lab (pictured below). Both devices were introduced to the public in Engelbart's 1968 demonstration, now known as the "Mother of All Demos" (see Check It Out below for links to selected video footage of the debut, historic photos, and more). 4b

1968 version includes three-button mouse and five-key keyset

1968 version includes three-button mouse and five-key keyset(click to enlarge) |

In Doug's Words: 4c

It was in the course of trying to broaden the bandwidth of the connection between humans and computers, incorporating both visual and motor skill dimensions, that I developed my most famous invention, the computer mouse.

The mouse we built for the [1968] show was an early prototype that had three buttons. We turned it around so the tail came out the top. We started with it going the other direction, but the cord got tangled when you moved your arm.

I first started making notes for the mouse in '61. At the time, the popular device for pointing on the screen was a light pen, which had come out of the radar program during the war. It was the standard way to navigate, but I didn't think it was quite right.

Two or three years later, we tested all the pointing gadgets available to see which was the best. Aside from the light pen there was the tracking ball and a slider on a pivot. I also wanted to try this mouse idea, so Bill English went off and built it.

We set up our experiments and the mouse won in every category, even though it had never been used before. It was faster, and with it people made fewer mistakes. Five or six of us were involved in these tests, but no one can remember who started calling it a mouse. I'm surprised the name stuck.

We also did a lot of experiments to see how many buttons the mouse should have. We tried as many as five. We settled on three. That's all we could fit. Now the three-button mouse has become standard, except for the Mac.

Mouse Alternatives 5

Engelbart and his team tested a half dozen pointing devices for speed and accuracy. These included the mouse, and a knee apparatus (pictured below, right), both created in-house, along with several off the shelf devices such as DEC's Grafacon (pictured below, center, modified for testing purposes), a joy stick, and a light pen. See Screen-Selection Experiments below for links to more details and photos. They also experimented with a foot pedal device as well as a head mounted device, neither of which made it into the final tests. 5a

| From Doug Engelbart's experiments with pointing devices in the mid 1960s |

||

DEC's gyro-stlye "Grafacon"

DEC's gyro-stlye "Grafacon" |

A knee-operated pointing device |

Joy stick and mouse |

A small piece of a large vision 6

In the 1950s, Doug Engelbart set his sights on a lofty goal -- to develop dramatically better ways to support intellectual workers around the globe in the daunting task of finding solutions to larger and larger problems with greater speed and effectiveness than ever before imagined. His goal was to revolutionize the way we work together on such tasks. He saw computers, at the time used primarily for number crunching, as a new medium for advancing the state of the art in collaborative knowledge work. Building on technology available at the time, his research agenda required that his team push the envelope on all fronts: they had to expand the boundaries of display technology and interactive computing and human-computer interface, help launch network computing, and invent hypermedia, groupware, knowledge management, digital libraries, computer supported software engineering, client-server architecture, the mouse, etc. on the technical front, as well as pushing the frontiers in process reengineering and continuous improvement, including inventing entirely new organizational concepts and methodologies on the human front. Engelbart even invented his own innovation strategy for accelerating the rate and scale of innovation in his lab which, by the way, proved very effective. His seminal work garnered many awards, and sparked a revolution that blossomed into the Information Age and the Internet. But as yet we have only scratched the surface of the true potential Engelbart envisioned for dramatically boosting our collective IQ in the service of humankind's greatest challenges. Check out his Call to Action and the Engelbart Academy to learn about his prescient message for the future. 6a

Genesis of the mouse:7

Doug's Early Vision:

From the introduction of his Augmenting

human intellect: A conceptual framework (1962):

7a

Let us consider an augmented architect at work. He sits at a working station that has a visual display screen some three feet on a side; this is his working surface, and is controlled by a computer (his "clerk") with which he can communicate by means of a small keyboard and various other devices. 7a1

He is designing a building. He has already dreamed up several basic layouts and structural forms, and is trying them out on the screen. The surveying data for the layout he is working on now have already been entered, and he has just coaxed the clerk to show him a perspective view of the steep hillside building site with the roadway above, symbolic representations of the various trees that are to remain on the lot, and the service tie points for the different utilities. The view occupies the left two-thirds of the screen. With a pointer he indicates two points of interest, moves his left hand rapidly over the keyboard, and the distance and elevation between the points indicated appear on the right-hand third of the screen. 7a2

From As

We May Think by Vannevar Bush, 1945 (quoted by Engelbart in Augmenting Human Intellect):

7b

"Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and to coin one at random, "memex" will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory. 7b1

"It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk. 7b2

Read more... and see how Engelbart was influenced by Vannevar Bush. 7b3

Debunking the Xerox PARC Mouse Myth 8

In the early 1970s, the mouse migrated from Doug's lab at SRI to Xerox PARC (along with some of his team), and later to Apple when Steve Jobs visited Xerox PARC, and beyond. One of the most common myths about the mouse is the mistaken belief that it was invented at Xerox PARC. Note that the first mouse was built in 1964, the patent for the mouse was filed in 1967, and demonstrated to an audience of over a thousand in 1968, by which time production models were in operational use throughout Doug's lab. Xerox PARC did not exist until 1970. 8a

See Also 9

Explore the Web 9a

Click for more Historic Firsts

Click for more Historic Firsts

|

- Visit Historic Firsts - for more of Doug Engelbart's many groundbreaking firsts; related to the Mouse, see especially Interactive Computing and The Keyset. 9a1

- MouseSite - the definitive website on the Mouse hosted by Stanford University, especially their Photos of the First Mouse page. They also curate video of the 1968 demo and other significant archives from Doug Engelbart's work. 9a2

- See the SRI Timeline on Innovation: Personal Computing + the Mouse, the SRI press release Engelbart and the Dawn of Interactive Computing (excellent overview), as well as our event resources page for Engelbart and the Dawn of Interactive Computing 9a3

- Visit the online exhibit on The Mouse at the Computer History Museum or visit their museum in Mt. View, CA; check out their Early Computer Mouse Encounters event at the Computer History Museum, Oct 17, 2001 9a4

- See the Mouse Timeline in The computer mouse turns 40 - a great article by Benj Edwards, Macworld, Dec 9, 2008 on the history of the Mouse. 9a5

- Visit Logitech's Billionth Mouse site - see the genesis of the mouse. 9a6

- Planimeter: Planimeters are devices used by surveyors, foresters, geologists, geographers, engineers, and architects to measure areas on maps of any kind and scale, as well as plans, blueprints, or any scale drawing or plan. (source: Ben Meadows). See How Planimeters Are Used for some great visuals (thanks to Dr. Robert Foote at Wabash College), and this photo of geographers using planimeter for the 1940 census (thanks to the National Archives). See also Wikipedia's more complete Planimeter article with links to other resources. 9a7

From Doug's Lab 9b

- Screen-Selection Experiments: Display-Selection Techniques for Text Manipulation, William K. English, Douglas C. Engelbart and Melvyn L. Berman, March 1967. This paper describes an experimental study into the relative merits of different CRT display-selection devices as used within a real-time, computer-display, text-manipulation system in use at Stanford Research Institute. The mouse was tested against other devices and found to be the most accurate and efficient. The paper is based on the 1965 Report, the 1965 User's Guide, and the 1966 Quarterly Report detailing their screen-selection experiments. 9b1

- Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework, Douglas C. Engelbart. 1962. See for example how he envisioned an architect might work interactively with a computer in 1962 in the Introduction's summary of Section IV (quoted at right). 9b2

- Doug Engelbart - A Lifetime Pursuit, a short biographical sketch by Christina Engelbart describes the larger context of this early work. 9b3